love

Appreciating Who We Are

A man who is living with Alzheimer’s strides onto the stage and people applaud wildly. His son leans across the drums and hands him his guitar. His daughter, poised on the banjo, subtly reminds the man to look at the monitor so he can remember the words to the songs.

Everyone on stage is tuned into making the performance a great experience for the man and everyone in the audience is eager to hear from him. “So what if he sings Rhinestone Cowboy twice,” says one fan.

This scene is a snippet from Glen Campbell’s documentary, “I’ll Be Me.” As I watched Glen connect through his familiar music and bask in the support of his family and fans, I wished that every person could be so supported and celebrated, particularly those who are living with dementia.

As we approach Valentine’s Day, I wanted to share this essay about appreciating each of us for who we are. For me, it’s a reminder to celebrate love and the creative spirit in all their glorious guises.

Please Take a Bow

By Deborah Shouse

The stage thrilled with activities. One man juggled 12 balls. From overhead, a woman floated down on streamers of royal blue fabric, and then wound herself back up to the arena ceiling. Lithe performers dressed as jungle animals danced and tumbled. I sat in the audience, awed by the amazing creativity of Cirque de Soleil. I hardly knew where to look, so much was going on. But one performer consistently drew my attention. A woman dressed as a wood nymph walked around pointing to whichever feat she most admired. As a man juggled dangerously long sticks, the nymph held out her arms toward him, her gesture saying, “Ta da, Look at this!”

The singer burst into an acrobatic aria and the wood nymph ran towards her, unfurling her arms in another “Ta Da” gesture, focusing our attention and directing our applause. One act after another somersaulted, soared and danced and the wood nymph was always there to shine extra attention on them.

Afterwards, I stood in the corridors with Ron and our friends, Jacqueline and Michael, talking over favorite parts of the show.

“I really liked the wood nymph,” I told Jacqueline. “We should take turns doing that for each other.”

She agreed. But then we both wondered, what would we applaud? Jacqueline and I did our writing work practically immobilized in front of the computer. Michael was a legal aid attorney and Ron had an antique shop. The last time any of us had even somersaulted was eons ago, in our firefly laden summertime back yards. Yes, we juggled, but it was the usual middle class shticks, wildly tossing around work, family, exercise, community, friends and more. All the more reason, I thought, to find an appreciator who understood when we performed at our personal peak.

As we discussed the amazing acrobatic skills we had just seen, I imagined going over to Jacqueline’s. There she sits at her dining room table, her computer screen bright, her fingers nimble. She is a great writer and she is working her craft. I stand nearby, face the imaginary audience seated in her living room, and hold out my arms, gesturing proudly towards Jacqueline. She smiles shyly and I hold my appreciative pose. Then Michael walks through on his way to the kitchen.

“Hi Deborah, what are you up to?” he says.

I nod towards Jacqueline, who is writing briskly, and unfurl my arms towards her.

“Oh, yes, I see,” Michael says. He applauds. Jacqueline sits up straighter and allows herself a little bow. A lot of people don’t understand what hard work writing is and I am here to make sure her audience appreciates the subtlety and strength of this art form. Suddenly, Jacqueline stops. I imagine a drum roll as she presses her lips together, furrows her brow and stares into space. She is trying to think of the right word. We all know how hard that is–it’s the equivalent of the back flip followed by the double mid-air somersault. She shakes her head in despair. The audience is on the edges of its seats, mouths agape, hearts racing. Will Jacqueline find the word? Or will she crash to the ground, her sentence in shambles, her paragraphs paralyzed?

Finally, Jacqueline grins and returns to the keyboard, her fingers dancing. I point to her—“TaDa”– and her audience erupts into applause.

Meanwhile, while I daydreamed, the Cirque de Soleil arena was emptying. We walked to our cars and the image of the wood nymph stayed with me all the way home.

As Ron and I walked toward our house, I remembered a conversation we’d had several weeks ago. “Why don’t you ever mention how great the yard looks?” he’d said. “I’ve worked hard on creating this.”

I had started to defend myself. Then I realized he was right. I liked the yard but its lushness was part of my normal world, the world I rushed blindly past. I hadn’t taken time to appreciate all the effort Ron had put into creating it.

Now I stopped on the sidewalk. The porch light illuminated the plants and ivy as I swept my arms toward the yard, then back to Ron.

“Ta da!” I said, pointing to his lawn, then applauding him. He stared at me, and then smiled.

“Thank you,” he said. “Thank you for noticing.” He took a bow.

I followed him as he left the stage and went into the house.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Four Reminders to Enjoy the Moment

Every week, I have the joy of interviewing a couple and learning their love story. We talk about where and when they met, what they like about each other, and how they stay connected during life’s chaos and challenges.

Recently, I talked to a couple who met in their late seventies. Both had lost their spouses and both were amazed to fall in love again. When I asked how they kept their relationship strong, she answered, “Because of our age, we know we don’t have that much time left to be together. We enjoy every moment of every day.”

Since that conversation, I have thought often about her words: What would it be like to truly appreciate every moment? What would it be like to completely appreciate each person I spent time with?

Being present and appreciative were two of my goals when I spent time with my mom in her later years. One moment, I felt connected, holding Mom’s hand, sitting right next to her while pointing out interesting pictures in a magazine, and the next moment her head would be lowered, her energy drained and I felt alone and sad. But of course, I wasn’t alone; I was right next to my mother, still holding her hand. My task was to enjoy that quiet minutes as much as the time that Mom was interacting with me.

“Enjoy every moment of every day.” These quotes echo that important reminder .

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Finding Comfort Where You Can

When I was in the throes of sadness following my divorce, my 12-year-old daughter came into my room and handed me a stuffed bear.

“This will help you,” she said.

At first, I had my doubts about the healing power of inanimate objects. But I soon learned that cuddling a soft bear was a calming and healing experience.

My mother created her own soothing experience when she was deep into Alzheimer’s. Here’s an excerpt from this story, from my book, Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

A Doll of Her Own

That afternoon, while my mother is walking down the left-hand side of the corridor in the Alzheimer’s unit, tapping one hand on the handrail, and pressing the other palm on her forehead, she sees a baby doll lying on the floor. Mom’s adult diaper rustles as she bends down, picks the baby up, smoothes its curly hair and carries it with her to the dining room. There she settles in a chair and rocks the baby, talking and singing to it.

“Your mom’s fallen in love with a baby doll,” Leticia, the nurse aide, says when I visit.

Mom is sitting at the table in the small dining room, her head bent over, as if she’s fallen asleep on a long journey. I touch her shoulder once, twice and on the third time, she straightens, notices me and smiles.

I sit beside her and spread out some photographs. She is staring vacantly at a photo of her granddaughters when Leticia brings over the baby doll.

“Here you go, Frances,” Leticia says.

Mom lights up, holds out her arms and says, “You’re cute. You’re so pretty. You’re a good boy. You’re a good girl.”

I look on in amazement. I haven’t seen Mom so animated in weeks. Yet I feel a pang: I had yearned to be the one who jolted her into vivacity.

I listen as Mom continues her conversation with the baby. Maybe the ease of having someone who doesn’t talk back, who doesn’t hope you will complete a sentence, who doesn’t care if the words are missing or not right, maybe that freedom lets Mom flow with her speech.

I decide to buy my mother her own baby doll.

At the toy store, the dolls are all full of activities. One laughs when you press her belly. One has a musical bottle. Another takes your picture …

I search the aisles for a quiet doll without too many accomplishments. Finally I find a soft, rosy-cheeked baby, a good size to cradle, who boasts only an open mouth for a pacifier or bottle.

“Some little girl is going to really enjoy this doll,” the cashier says as I pay.

I smile as I envision that 87-year-old little girl who is my mother.

Mom sits in a chair in the TV room, eating strawberry ice cream out of a round cardboard container. I know better than to compete with dessert, so I wait until she has finished the last smidgen.

Then I put my hand on her shoulder. She looks at me, her eyes vacant.

“Hi, Mom,” I say. She stares at me and then she sees the baby doll.

“You’re here,” she says, her eyes widening. “My little girl is here.”

She holds out her arms and I hand her the baby.

“Bo bo bupe, tootle ootle, oop. I have my little girl,” she croons.

She smiles at me; she smiles at the doll. Does she know I’m her real little girl or is she imagining the doll as her child? At this moment, as I watch my mother come to life and praise her baby, it simply doesn’t matter.

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Many a Quote to Keep us Afloat

Please God, Please, don’t let me be normal!”

When I was growing up, my friend Susan and I often chanted this line from the Fantastiks. For us, normal meant mundane and we envisioned ourselves living daringly on the creative cusps.

During my time as a family caregiver, I often yearned for more of that mythical “normal.” Yet, I also wanted to be connected to my creative spirit. These are some of the words of wisdom that I used for infusions of inspiration. I’d love to hear from you: what quotes keep you afloat?

“Be recklessly generous and relentlessly kind.” Pam Grout

“It’s never too late to be what you might have been.” George Eliot

“May all beings be happy. May all my thoughts, words and actions contribute in some way to the happiness of all beings.” Lokah Samasta Sukhino Bhavantu:

These two quotes remind me to open my heart and dream.

“My great hope is to laugh as much as I cry; to get my work done and try to love somebody and have the courage to accept the love in return.” Maya Angelou

“Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things that you didn’t do than by the ones you did do. So throw off the bowlines. Sail away from the safe harbor. Catch the trade winds in your sails. Explore. Dream. Discover.” (Mark Twain)

Deborah Shouse is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.

Sharing Stories and Songs

“To love a person is to learn the song that is in their heart,

And to sing it to them when they have forgotten.”

~ Arne Garborg

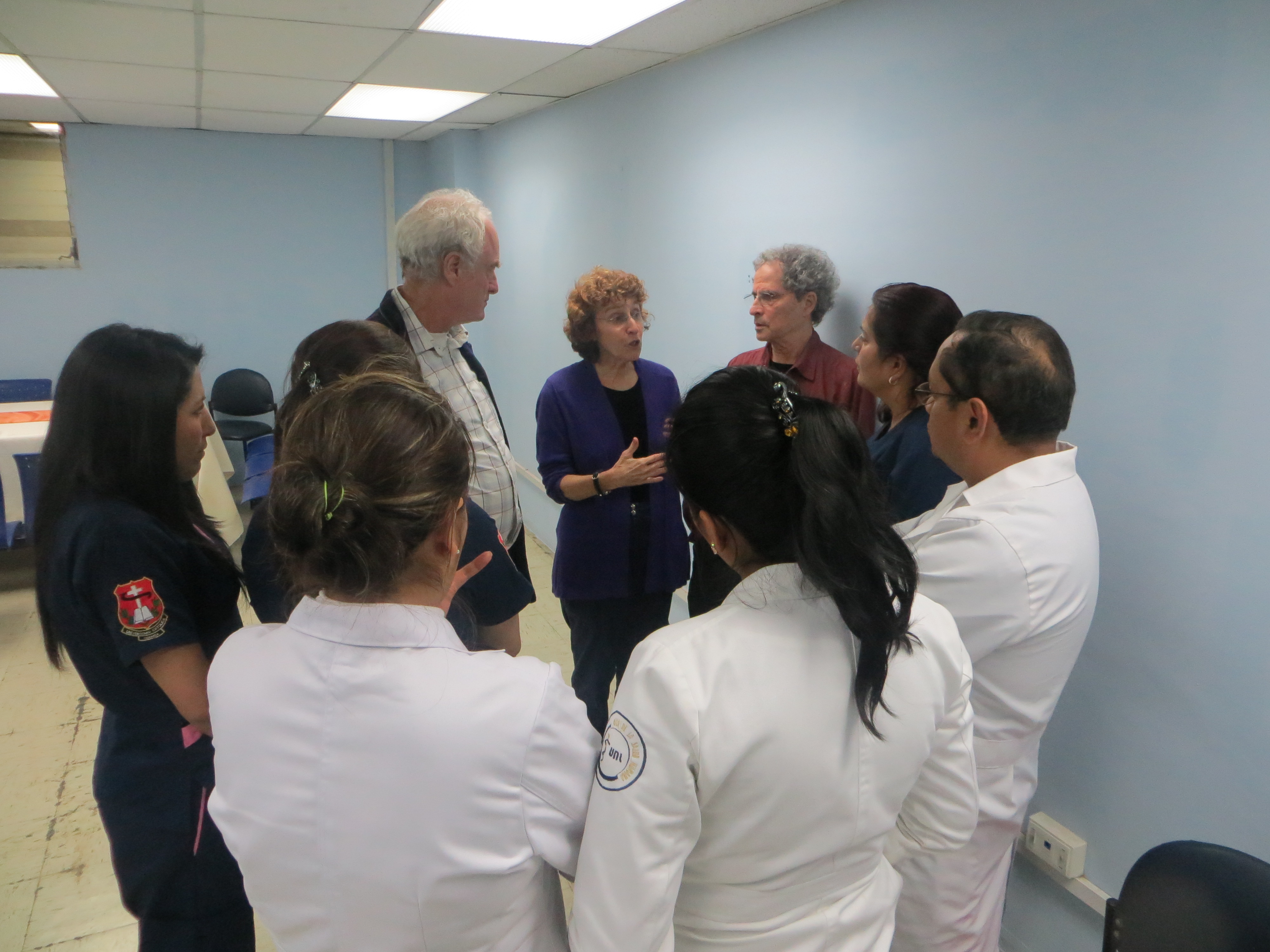

At our recent Alzheimer’s performance at the Isidro Ayora Hospital in Loja, Ecuador, we shared stories and ideas and learned how these health care professionals were dealing with clients who had dementia.

One nurse described her close relationship with an elderly client. “I feel like I’m a partner with the family in caring for her,” she said.

“I’m interested in integrating more kinds of therapies, such as music and art therapies, into our care,” a doctor commented.

“I’m looking for ways to reduce the stress of being a caregiver,” another member of the team said.

We had a lively and meaningful conversation and we were impressed by their dedication and caring.

If you have tips for reducing the stress of being a caregiver, we welcome your comments and we’ll share them with our friends in Ecuador and elsewhere.

myinfo@pobox.com

816-361-7878

Follow us on Twitter: @DeborahShouse

What I Have Learned about Love: Moments of Indelible Beauty

The canoe slips through the narrow passageway just as the sun touches the water. As we round a corner, we spot a black-capped heron, poised for fishing, elegant with its delicate feathery head plume, powdery blue beak and long ivory body. He stares at us for a moment and then lifts his grand wings and disappears into the groves of elephant ear trees. Though we see him for only a few seconds, his beauty stays with us throughout the day.

So many times, when my mother was deep into her Alzheimer’s journey, I rounded a corner and had a glimpse of her true depth and beauty. Then, like the heron, she disappeared into her own personal forest. But the image of her shining face and the excitement of the momentary connection remained with me.

This month, I’m going to write about one of my favorite topics—love. I’m asking myself, “What have I learned about love by knowing and caring for people who have Alzheimer’s?” I welcome your answers to that question.

Five Ways to Make Valentine’s Day Special for a Loved One with Dementia

My parents liked to celebrate Valentine’s Day with dinner and dancing. Years into my mom’s Alzheimer’s journey, my parents’ love hadn’t diminished, but my mom’s capacity for going out to dinner and dancing had drastically decreased. I saw how blue my father was—one more event he had to give up, one more change in the woman he loved—and I searched for alternatives that might cheer him up. Here are a few things we tried:

Look for a favorite thing. Seek one simple pleasure your loved one might enjoy. Mom loved potato soup and chocolate and fresh strawberries. These were part of our celebration.

Nurture yourself: include your own favorite thing. Bring yourself into the celebration and include something that makes you happy. I brought foods my father and I both liked as part of our little party.

Pick several ways to express your love. Poetry, music, gifts, flowers, and photo albums—you can use any of these resources as a catalyst to talk about your feelings. Dad and I sang Mom old show tunes and love songs, music she really enjoyed. Mom adored Shakespeare; we had a couple of sonnets on hand. She and Dad had once created a beautiful flower garden; Dad brought her a single red rose.

Take joy in the simple act of expressing yourself. Being with my mom was a chance to really practice the mythical “unconditional love.” Mom couldn’t tell me she loved me. During one Valentine’s Day celebration, she fell asleep while I was holding her hand and talking sweetly to her. But there was a comfort in expressing my love and I kept on talking.

Celebrate love in all its glorious guises. During their long marriage, my father had walked into a room millions of times and often, Mom had been busy and hadn’t particularly smiled or remarked. But with her dementia came a deep dependency on Dad. When Dad walked into a room, my mother’s face lit up. My father basked in that light. The sparkle in my mother’s eyes was the new, “I love you, darling.” The light said everything my mother could no longer say.

Deborah is the author of Love in the Land of Dementia: Finding Hope in the Caregiver’s Journey.